Displaying items by tag: Animal Camp

Do you enjoy Nature? Do you like to take pictures?

Now it’s your chance to make the call! The National Wildlife Federation needs your vote!

Their Magazine has selected the finalists for this Photo Contest. The theme is “Nature in My Neighborhood.” Now we need YOU to help choose the winner!

Vote for your favorite image today! The top vote-getter receives an official NWF field guide and, if not already a member, a free one-year membership to National Wildlife Federation. But we need to hear from you soon: Voting ends April 15!

Hey!

Jacob here, I will be in the Nature Center this summer teaching you all about the big beautiful outdoors.. I like to fish, hunt and play sports. This is my first summer at camp but at school I’m studying youth programming and camp management. I love being outside and making new friends... ( this is my new friend here in the picture :) It is going to be a great summer!

permalink=”http://www.swiftnaturecamp.com/blog”>

Despite this awareness of Nature and the Environment there is a staggering divide between children and the outdoors, child advocacy expert Richard Louv directly links the lack of nature in the lives of today's wired generation-he calls it nature-deficit-to some of the most disturbing childhood trends, such as the rises in obesity, attention disorders, and depression.

Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder has spurred a national dialogue among educators, health professionals, parents, developers and conservationists. This is a book that will change the way you think about your future and the future of your children. The bottom Line we and our youth need to spend time outdoors.

Schools have realized this for some time. Teacher Judith Millar, Lucy Holman School, Jackson, NJ, more than five years ago, began an environmental project in the school's courtyard. It has become quite an undertaking--even gaining state recognition. It contains several habitat areas, including a Bird Sanctuary, a Hummingbird/ Butterfly Garden, A Woodland Area with a pond, and a Meadow. My classes have always overseen the care of this "Outdoor Classroom", but now it's practically a full time job!! My students currently maintain the Bird Sanctuary--filling seed and suet feeders, filling the birdbaths, building birdhouses, even supplying nesting materials! In addition, this spring they will be a major force in the clean up and replanting process. They always have energy and enthusiasm for anything to do with "their garden".

Despite schools doing their best to get kids to play outside, we as a nation have lost the ability to just send our kids out to play. Yet, it seems we are learning that Summer Camps help children grow into mature adults. A new British study finds that most modern parents overprotect their kids. Half of all kids have stopped climbing trees, and 17 percent have been told that they can't play tag or chase. Even hide-and-seek has been deemed dangerous. And that dreaded stick..."will put out someone's eye".

It is easy to blame technology for the decline in outdoor play, but it may well be mom and dad. Adrian Voce of Play England says 'Children are not being allowed many of the freedoms that were taken for granted when we were children,' 'They are not enjoying the opportunities to play outside that most people would have thought of as normal when they were growing up.'

According to the Guardian, "Voce argued that it was becoming a 'social norm' for younger children to be allowed out only when accompanied by an adult. 'Logistically that is very difficult for parents to manage because of the time pressures on normal family life,' he said. 'If you don't want your children to play out alone and you have not got the time to take them out then they will spend more time on the computer.'

The Play England study quotes a number of play providers who highlight the benefits to children of taking risks. 'Risk-taking increases the resilience of children,' said one. 'It helps them make judgments,' said another. We as parents want to play it safe and we need to rethink safety vs adventure.

The research also lists examples of risky play that should be encouraged including fire-building, den-making, watersports, paintballing, boxing and climbing trees. Summer camp provides an excellent opportunity for children to get outside take risks and play, all while still while being supervised by concerned young adults...knowen as counselors.

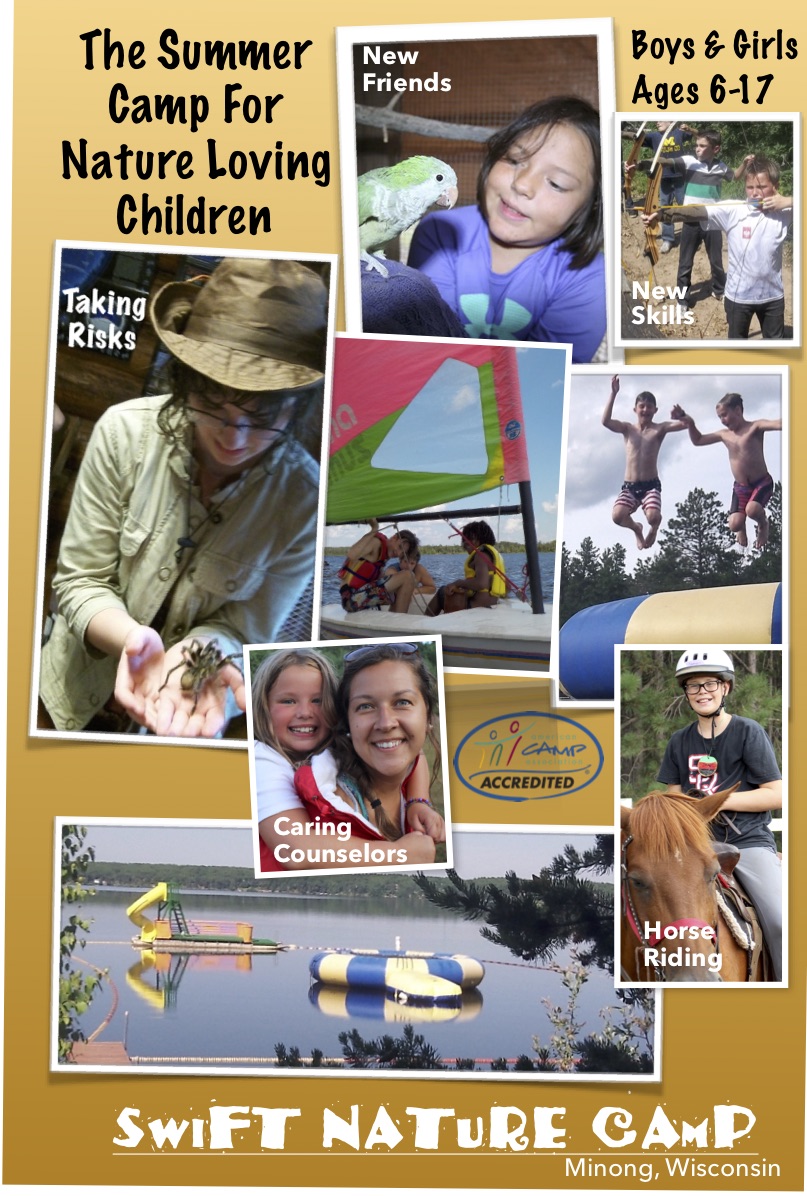

Swift Nature Camp is a Noncompetitive, Traditional Summer Nature Campin Wisconsin. Our Boys and Girls Ages 6-15. enjoy Nature, Animals & Science along with Traditional camping activities. We places a very strong emphasis on being an ENVIRONMENTAL CAMP where we develop a desire to know more about nature but also on acquiring a deep respect for it. Our educational philosophy is to engage children in meaningful, fun-filled learning through active participation. We focus on their natural curiosity and self-discovery. This is NOT School.

No matter what skill level or interests your children have, Swift Nature Camp has activities that allows them to excel and enjoy. All activities are promoted in a nurturing, noncompetitive atmosphere, giving each camper the opportunity to participate and have fun, rather than worry about results.

Campers also can participate in out-of-camp trips, such as biking, canoeing, backpacking and horse trips. This is the ultimate test of a camper's skill and knowledge. It's a reward to discover new worlds and be comfortable in them. This is what makes S.N.C. so much more than just aSCIENCE SUMMER CAMP.

Earth day has provided so much..but their is more we can learn from nature. This summer help your child regain their appreciation for nature by sending them to Swift Nature Camp. This is an opportunity that will be treasured the rest of your child's life.

supports the implementation of Wisconsin’s Plan for Environmental Literacy and Sustainable

Communities . This plan is the latest in a long line of environmental education initiatives in the

state . Beginning with the Conservation Movement in the late 1800s and early 1900s through

the Environmental Movement in the 1960s and 70s and on to today, residents of Wisconsin

have played a key role in shaping the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of individuals, groups,

and organizations with respect to environmental issues at the national, regional, and local

levels . As a new century has just begun, this plan provides a pathway for all of us to build

upon this prior work and move forward in developing an environmentally literate society

comprised of sustainable communities .

permalink=”http://www.swiftnaturecamp.com/blog”>

Sustainable Communities (referred to in this document

as the “Plan”) serves as a strategic plan for achieving

the vision of environmentally literate and sustainable

communities across Wisconsin . The Plan is meant to

build capacity, awareness, and support for environmental

literacy and sustainability at home, work, school, and

play . It encourages funding, research, and education for

environmental literacy and sustainability and it supports

Wisconsin’s Plan to Advance Education for Environmental

Literacy and Sustainability in PK-12 Schools.

This Plan was developed through input from diverse

representatives from around the state, all of whom—

like many before them—are attentive to the health and

well-being of Wisconsin’s people, the stewardship of our

natural resources, the sustainability of our communities,

and to leaving a positive legacy for the future . Wisconsin

people value the state’s natural resources and the functions

these resources serve at home, work, school, and play .

This commitment to protecting and conserving valued

resources can and does lead to sustainable communities

that enjoy a healthy environment, a prosperous economy,

and a vibrant civic life . The purpose of this Plan, therefore,

is to provide a roadmap, a course of action, individuals,

organizations, businesses and governments must

take to attain environmental literacy and sustainable

communities . By providing a shared vision, mission,

and goals, encouraging the use of common language,

and promoting collaborative efforts, the Plan offers the

opportunity for extraordinary impact and change .

The Wisconsin Environmental Education Board (WEEB) is charged with

leadership for environmental education for all people in the state and is required

to develop a strategic plan every ten years . This Plan was born from that

demand . WEEB’s previous strategic plan, A Plan for Advancing Environmental

Education in Wisconsin: EE2010, had seven goals that were based on the central

purposes of providing positive leadership; developing local leaders; developing

and implementing curricula; and furthering professional development .

An assessment provided insight into this plan’s successes and what remains to be

done . Major successes include:

• The creation of a website, EEinWisconsin .org, which acts as a tool for

statewide communication and a clearinghouse for both formal and non-

formal environmental education in Wisconsin .

• The WEEB’s use of the goals in its grants program .

• The initiation of research in environmental literacy and sustainability .

• The establishment of Wisconsin Environmental Education Foundation,

which is leading the way toward more sustainable funding for

environmental education .

The assessment found more work needs to be done to support and enhance

non-formal and non-traditional environmental education . The Plan addresses

this need and sets new goals .

Collaboration with Other Efforts

considers educational needs and responses for the whole community and

supports sustainable practices at home, work, school, and play . The Plan is

coordinated with and supported by two additional statewide efforts to advance

the implementation of the Plan’s goals and the integration of sustainability . They

are:

Wisconsin’s Plan to Advance Education for Environmental Literacy and

Sustainability in PK-12 Schools addresses multiple aspects related directly

to pre-kindergarten through high school student learning to ensure every

student graduates environmentally literate . (NCLIwisconsin .org)

Cultivating Education for Sustainability in Wisconsin builds capacity

and support for schools and communities to focus student learning on

sustainability . It provides recommendations for resources and services to

implement education for sustainability in schools . (www .uwsp .edu/wcee/efs)

2 Wisconsin’s Plan for Environmentally Literate and Sustainable Communities

Benefits of a State Plan

• Provide a common vision and set of goals for people in Wisconsin to work

toward .

• Guide decision-making, policy making and priority setting .

• Serve as justification for and purpose behind creating or continuing

programs, tools and resources .

• Set priorities for development and delivery of educational programs,

business plans, and community efforts .

• Rationale and guidance for funding and research efforts .

How to Use the Plan

Wisconsin’s Plan for Environmentally Literate and Sustainable Communities is

not an organization, but rather a document that serves as the state strategic plan

requiring partnerships and collaboration . It is designed to serve as reference

material for individuals, businesses, and communities . Those who influence

environmental literacy and sustainability in Wisconsin such as community

leaders, traditional and non-formal educators and administrators, resources

developers and providers, policy makers, funders and researchers will find the

Plan useful as a guide in setting priorities and making decisions . Over the course

of the next decade, the Plan’s desired outcomes will be central to environmental

literacy and sustainability efforts across the state . As Wisconsin people work

toward achieving the four main outcomes of the Plan, this document can help

guide attitudes, planning, actions, and endeavors .

Eurasian Water Milfoil

Eurasian milfoil first arrived in Wisconsin in the 1960's. During the 1980's, it began to move from southern Wisconsin to lakes and waterways in the northern half of the state. This migration took place mainly by boaters not removing fragments from their boats as they went from lake to lake. In Minong Wisconsin. the milfoil increase has happened over the last 10 years or so. Today, many lakes in the region are trying many ways to eliminate this nonnative invasive species.

Eurasian Water Milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum)

DESCRIPTION: Eurasian water milfoil is a submersed aquatic plant native to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. It is the only non-native milfoil in Wisconsin. Like most of the native milfoils, the Eurasian variety has slender stems whorled by submersed feathery leaves. The stems of Eurasian water milfoil tend to be limp, and may show a pinkish-red color. The 4-petaled, pink flowers of Eurasian water milfoil are located on a spike that rises a few inches out of the water. The leaves are typically divided into 12 or more pairs of threadlike leaflets. The most common native water milfoils tend to have whitish or brownish stems, and leaves that divide into fewer than 10 pairs of leaflets. Coontail is often mistaken for the milfoils, but its leaves are not feathery, but rather branch once or twice with several small teeth along the leaves. Bladderworts can also be mistaken for Eurasian watermilfoil, but they are easily distinguished by the presence of many small bladders on the leaves, which serve to trap and digest small aquatic insects.

|

|

DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT: Eurasian milfoil first arrived in Wisconsin in the 1960's. During the 1980's, it began to move from several counties in southern Wisconsin to lakes and waterways in the northern half of the state. As of 1993, Eurasian milfoil was common in 39 Wisconsin counties (54%) and at least 75 of its lakes, including shallow bays in Lakes Michigan and Superior and Mississippi River pools.

Eurasian water milfoil grows best in fertile, fine-textured, inorganic sediments. In less productive lakes, it is restricted to areas of nutrient-rich sediments. It has a history of becoming dominant in eutrophic, nutrient-rich lakes, although this pattern is not universal. It is an opportunistic species that prefers highly disturbed lake beds, lakes receiving nitrogen and phosphorous-laden runoff, and heavily used lakes. Optimal growth occurs in alkaline systems with a high concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon. High water temperatures promote multiple periods of flowering and fragmentation.

LIFE HISTORY AND EFFECTS OF INVASION: Unlike many other plants, Eurasian water milfoil does not rely on seed for reproduction. Its seeds germinate poorly under natural conditions. It reproduces vegetatively by fragmentation, allowing it to disperse over long distances. The plant produces fragments after fruiting once or twice during the summer. These shoots may then be carried downstream by water currents or inadvertently picked up by boaters. Milfoil is readily dispersed by boats, motors, trailers, bilges, live wells, or bait buckets, and can stay alive for weeks if kept moist.

Once established in an aquatic community, milfoil reproduces from shoot fragments and stolons (runners that creep along the lake bed). As an opportunistic species, Eurasian water milfoil is adapted for rapid growth early in spring. Stolons, lower stems, and roots persist over winter and store the carbohydrates that help milfoil claim the water column early in spring, photosynthesize, divide, and form a dense leaf canopy that shades out native aquatic plants. Its ability to spread rapidly by fragmentation and effectively block out sunlight needed for native plant growth often results in monotypic stands. Monotypic stands of Eurasian milfoil provide only a single habitat, and threaten the integrity of aquatic communities in a number of ways; for example, dense stands disrupt predator-prey relationships by fencing out larger fish, and reducing the number of nutrient-rich native plants available for waterfowl.

Dense stands of Eurasian water milfoil also inhibit recreational uses like swimming, boating, and fishing. Some stands have been dense enough to obstruct industrial and power generation water intakes. The visual impact that greets the lake user on milfoil-dominated lakes is the flat yellow-green of matted vegetation, often prompting the perception that the lake is "infested" or "dead". Cycling of nutrients from sediments to the water column by Eurasian water milfoil may lead to deteriorating water quality and algae blooms of infested lakes.

CONTROLLING EURASIAN WATER MILFOIL: Preventing a milfoil invasion involves various efforts. Public awareness of the necessity to remove weed fragments at boat landings, a commitment to protect native plant beds from speed boaters and indiscriminate plant control that disturbs these beds, and a watershed management program to keep nutrients from reaching lakes and stimulating milfoil colonies--all are necessary to prevent the spread of milfoil.

Monitoring and prevention are the most important steps for keeping Eurasian water milfoil under control. A sound precautionary measure is to check all equipment used in infested waters and remove all aquatic vegetation upon leaving the lake or river. All equipment, including boats, motors, trailers, and fishing/diving equipment, should be free of aquatic plants.

Lake managers and lakeshore owners should check for new colonies and control them before they spread. The plants can be hand pulled or raked. It is imperative that all fragments be removed from the water and the shore. Plant fragments can be used in upland areas as a garden mulch.

DNR permits are required for chemical treatments, bottom screening, buoy/barrier placement, and mechanized removal.

Mechanical Control: Mechanical cutters and harvesters are a common method for controlling Eurasian water milfoil in Wisconsin. While harvesting may clear out beaches and boat landings by breaking up the milfoil canopy, the method is not selective, removing beneficial aquatic vegetation as well. These machines also create shoot fragments, which contributes to milfoil dispersal. Harvesting should be used only after colonies have become widespread, and harvesters should be used offshore where they have room to turn around. Hand cutters work best inshore, where they complement hand pulling and bottom screening. A diver-operated suction dredge can be used to vacuum up weeds, but the technique can destroy nearby native plants and temporarily raise water turbidity.

Hand pulling is the preferred control method for colonies of under 0.75 acres or fewer than 100 plants. The process can be highly effective at selectively removing Eurasian water milfoil if done carefully; special care must be taken to collect all roots and plant fragments during removal. Hand pulling is a time-consuming process.

Bottom screening can be used for small-scale and localized infestations on sites with little boat traffic, but will kill native vegetation as well. The bottom screens are anchored firmly against the lake bed to kill grown shoots and prevent new sprouts, but screens must be removed each fall to clean off sediment that encourages rooting. Buoys can mark identified colonies and warn boaters to stay away. Bottom screens may exacerbate a milfoil population once removed, because Eurasian water milfoil will readily re-colonize the bare sediment.

Whenever possible, milfoil control sites should become customized management zones. For example, milfoil removal by harvesting can be followed by planting native plants to stabilize sediments against wave action, build nurseries for fry, attract waterfowl, and compete against new milfoil invasions.

Chemical Control: Herbicide treatments are commonly used to control Eurasian water milfoil. While no herbicide treatment is completely selective for milfoil, timing treatment early in the spring as soon as water warms helps limit unintentional harm to native plants. Herbicide treatments are most effective combined with vigilant post-treatment monitoring and non-chemical controls such as hand-pulling milfoil as it returns. When used carelessly, chemical treatments can be disruptive to aquatic ecosystems, not selective in the vegetation affected, and can cause more harm than good.

Biological Control: Eurhychiopsis lecontei, an herbivorous weevil native to North America, has been found to feed on Eurasian water milfoil. Adult weevils feed on the stems and leaves, and females lay their eggs on the apical meristem (top-growing tip); larvae bore into stems and cause extensive damage to plant tissue before pupating and emerging from the stem. Three generations of weevils hatch each summer, with females laying up to two eggs per day. It is believed that these insects are causing substantial decline in some milfoil populations. Because this weevil prefers Eurasian water milfoil, other native aquatic plant species, including northern water milfoil, are not at risk from the weevil's introduction. Twelve Wisconsin lakes are currently part of a two-year DNR project studying the weevil's effectiveness in curbing Eurasian water milfoil populations. The fungus Mycoleptidiscus terrestris is also under extensive research.

Gray wolf factsheet

- Legal status in U.S.: Federally delisted since January 27, 2012. Currently a "Protected Wild Animal" in Wisconsin.

- 2011 Numbers in Wisconsin: ~800

- Length: 5.0-5.5 feet long (including 15-19 inch tail)

- Height: 2.5 feet high

- Weight: 50-100 pounds/average for adult males is 75 pounds, average for adult females is 60 pounds.

Description

Gray wolves, also referred to as timber wolves, are the largest wild members of the dog family. Males are usually bigger than females. Wolves have many color variations but tend to be buff-colored tans grizzled with gray and black (although they can also be black or white). In winter, their fur becomes darker on the neck, shoulders and rump. Their ears are rounded and relatively short, and the muzzle is large and blocky. Wolves generally hold their tail straight out from the body or down. The tail is black tipped and longer than 18 inches.

Wolves can be distinguished by tracks and various physical features. A wolf, along other wild canids, usually places its hind foot in the track left by the front foot, whereas a dog's front and hind foot tracks usually do not overlap each other. See the wolf identification page for more details.

Thumbnails link to larger images.

Habits

A wolf pack's territory may cover 20-120 square miles, about one tenth the size of an average Wisconsin county. Thus, wolves require a lot of space in which to live, a fact that often invites conflict with humans.

While neighboring wolf packs might share a common border, their territories seldom overlap by more than a mile. A wolf that trespasses in another pack's territory risks being killed by that pack. It knows where its territory ends and another begins by smelling scent messages - urine and feces - left by other wolves. In addition, wolves announce their territory by howling. Howling also helps identify and reunite individuals that are scattered over their large territory.

How does a non-breeding wolf attain dominant, or breeding status? It can stay with its natal pack, bide its time and work its way up the dominance hierarchy. Or it can disperse, leaving the pack to find a mate and a vacant area in which to start its own pack. Both strategies involve risk. A bider may be out-competed by another wolf and never achieve dominance. Dispersers usually leave the pack in autumn or winter, during hunting and trapping season.

Dispersers must be alert to entering other wolf packs' territories, and they must keep a constant vigil to avoid encounters with people, their major enemy. Dispersers have been known to travel great distances in a short time. One radio-collared Wisconsin wolf traveled 23 miles in one day. In ten months, one Minnesota wolf traveled 550 miles to Saskatchewan, Canada. A female wolf pup trapped in the eastern part of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, died from a vehicle collision near Johnson Creek in Jefferson County, Wisconsin in March 2001, about 300 miles from her home territory.

Nobody knows why some wolves disperse and others don't. Even siblings behave differently, as in the case of Carol and Big Al, radio-collared yearling sisters in one Wisconsin pack. Carol left the pack one December, returned in February, then dispersed 40 miles away. Big Al remained with the pack and probably became the pack's dominant female when her mother was illegally shot.

In another case, two siblings dispersed from their pack, but did so at different times and in different directions. One left in September and moved 45 miles east and the other went 85 miles west in November.

Food

Timber wolves are carnivores feeding on other animals. A study in the early 1980s showed that the diet of Wisconsin wolves was comprised of 55 percent white-tailed deer, 16 percent beavers, 10 percent snowshoe hares and 19 percent mice, squirrels, muskrats and other small mammals. Deer comprise over 80 percent of the diet much of the year, but beaver become important in spring and fall. Beavers spend a lot of time on shore in the fall and spring, cutting trees for their food supply. Since beavers are easy to catch on land, wolves eat more of them in the fall and spring than during the rest of the year. In the winter, when beavers are in their lodges or moving safely beneath the ice, wolves rely on deer and hares. Wolves' summer diet is more diverse, including a greater variety of small mammals.

Breeding biology

Wolves are sexually mature when two years old, but seldom breed until they are older. In each pack, the dominant male and female are usually the only ones to breed. They prevent subordinate adults from mating by physically harassing them. Thus, a pack generally produces only one litter each year, averaging five to six pups.

In Wisconsin, wolves breed in late winter (late January and February). The female delivers the pups two months later in the back chamber of a den that she digs. The den's entrance tunnel is 6-12 feet long and 15-25 inches in diameter. Sometimes the female selects a hollow log, cave or abandoned beaver lodge instead of making a den.

At birth, wolf pups are deaf and blind, have dark fuzzy fur and weigh about 1 pound. They grow rapidly during the first three months, gaining about 3 pounds each week. Pups begin to see when two weeks old and can hear after three weeks. At this time, they become very active and playful.

When about six weeks old, the pups are weaned and the adults begin to bring them meat. Adults eat the meat at a kill site often miles away from the pups, then return and regurgitate the food for the pups to eat. The hungry pups jump and nip at the adults' muzzles to stimulate regurgitation.

The pack abandons the den when the pups are six to eight weeks old. The female carries the pups in her mouth to the first of a series of rendezvous sites or nursery areas. These sites are the focus of the pack's social activities for the summer months and are usually near water.

By August, the pups wander up to two to three miles from the rendezvous sites and use them less often. The pack abandons the sites in September or October and the pups, now almost full-grown, follow the adults.

Photos of wolf pups at a den site

Thumbnails link to larger images.

Distribution

Before Europeans settled North America, gray wolves inhabited areas from the southern swamps to the northern tundra, from coast to coast. They existed wherever there was an adequate food supply. However, people overharvested wolf prey species (e.g., elk, bison and deer), transformed wolf habitat into farms and towns and persistently killed wolves. As the continent was settled, wolves declined in numbers and became more restricted in range. Today, the majority of wolves in North America live in remote regions of Canada and Alaska. In the lower 48 states, wolves exist in forests and mountainous regions in Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Washington, Arizona, New Mexico, North Dakota, and possibly in Oregon, Utah and South Dakota.

Map showing wolf distribution

History in Wisconsin

Before Wisconsin was settled in the 1830s, wolves lived throughout the state. Nobody knows how many wolves there were, but best estimates would be 3,000-5,000 animals. Explorers, trappers and settlers transformed Wisconsin's native habitat into farmland, hunted elk and bison to extirpation, and reduced deer populations. As their prey species declined, wolves began to feed on easy-to-capture livestock. As might be expected, this was unpopular among farmers. In response to pressure from farmers, the Wisconsin Legislature passed a state bounty in 1865, offering $5 for every wolf killed. By 1900, no timber wolves existed in the southern two-thirds of the state.

At that time, sport hunting of deer was becoming an economic boost to Wisconsin. To help preserve the dwindling deer population for this purpose, the state supported the elimination of predators like wolves. The wolf bounty was increased to $20 for adults and $10 for pups. The state bounty on wolves persisted until 1957. By the time bounties were lifted, millions of taxpayers' dollars had been spent to kill Wisconsin's wolves, and few wolves were left. By 1960, wolves were declared extirpated from Wisconsin. Ironically, studies have shown that wolves have minimal negative impact on deer populations, since they feed primarily on weak, sick, or disabled individuals.

The story was similar throughout the United States. By 1960, few wolves remained in the lower 48 states (only 350-500 in Minnesota and about 20 on Isle Royale in Michigan). In 1974, however, the value of timber wolves was recognized on the federal level and they were given protection under the Endangered Species Act [exit DNR]. With protection, the Minnesota wolf population in-creased and several individuals dispersed into northern Wisconsin in the mid-1970s. In 1975, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources declared timber wolves endangered.

Intense monitoring of wolves in Wisconsin by the DNR began in 1979. Attempts were made to capture, attach radio collars and radio-track wolves from most packs in the state. Additional surveys were done by snow-tracking wolf packs in the winter and by howl surveys in the summer. In 1980, 25 wolves in 5 packs occurred in the state, but dropped to 14 in 1985 when parvovirus reduced pup survival and killed adults. Wisconsin DNR completed a wolf recovery plan in 1989. The recovery plan set a state goal for reclassifying wolves as threatened once the population remained at or above 80 for three years. Recovery efforts were based on education, legal protection, habitat protection, and providing compensation for problem wolves.

In the 1990s the wolf population grew rapidly, despite an outbreak of mange between 1992 -1995. The DNR completed a new management plan in 1999. This management plan set a delisting goal of 250 wolves in late winter outside of Indian reservations, and a management goal of 350 wolves outside of Indian reservations. In 1999, wolves were reclassified to state threatened status with 205 wolves in the state. In 2004 wolves were removed from the state threatened species list and were reclassified as a protected wild animal with 373 wolves in the state.

Current status (as of April 2012)

The wolf is a "Protected Wild Animal" in Wisconsin. After five years of delisting attempts and subsequent court challenges, a new federal delisting process began on May 5, 2011 and wolves were officially delisted on January 27, 2012. The count in winter 2011 was about 782-824 wolves with 202-203 packs, 19-plus loners, and 31 wolves on Indian reservations in the state.

Misconceptions and controversies

Wolves are the "bad guys" of fable, myth and folklore. The "big bad wolf" fears portrayed in "Little Red Riding Hood," "Peter and the Wolf" and other tales have their roots in the experiences and stories of medieval Europe. Wolves were portrayed as vile, demented, immoral beasts. These powerful negative attitudes and misconceptions about wolves have persisted through time, perpetuated by stories, films and word-of-mouth, even when few Americans will ever have the opportunity to encounter a wolf.

Wolves are controversial because they are large predators. Farmers are concerned about wolves preying on their livestock. In northern Wisconsin, about 50-60 cases of wolf depredation occur per year, about half are on livestock and half on dogs. As the population continues to increase, slight increases in depredation are likely to occur. In Minnesota, with about 3,000 wolves, there are usually 60 to 100 cases per year.

A few hunters continue to illegally kill wolves, believing that such actions will help the deer herd. It is important to place in perspective the impact of wolves preying on deer. Each wolf kills about 20 deer per year. Multiply this by the number of wolves found in Wisconsin in recent years (800), and approximately 16,000 deer may be consumed by wolves annually. This compares to about 27,000 deer hit by cars each year, and about 340,000 deer shot annually by hunters statewide. Within the northern and central forests where most wolves live, wolves kill similar numbers of deer as are killed by vehicles (about 8,000), and about 1/10 of those killed by hunters (8,000 in 2010). Wolves are a factor in the deer herd, but only one of many factors that affects the total number of deer on the landscape.

Research and management

The Wisconsin DNR has been studying wolves since 1979 by live capturing, attaching radio collars and monitoring movements. Much has been learned about wolf ecology in northern Wisconsin. In 1992, the department began a research project to determine the impact of highway development in northwest Wisconsin on wolves. A Geographic Information System, (computer mapping system) was used to determine that northern Wisconsin has about 6,000 square miles of habitat that could support 300-500 wolves. Recent studies suggest the state can perhaps support 700 to 1,000 wolves (in late winter), but this level may not be socially tolerated and recent federal delisting of wolves will allow the department to manage the wolf population toward sustainable but acceptable population levels.

The DNR recognizes wolves as native wildlife species that are of value to natural ecosystems and benefit biological diversity of Wisconsin. The department approved a Wolf Recovery Plan in 1989. The plan's goal of 80 wolves was first achieved in 1995 mainly through protection and public education programs, and did not require any active reintroductions into the state. In 1999, wolves were reclassified to threatened in Wisconsin, and a new wolf management plan was approved that set a state delisting goal at 250 and management goal at 350 wolves in late winter outside of Indian reservations. The wolf management goal represents a threshold level that allows the Department to use a full range of lethal controls, including public harvest, to manage the wolf population. Wolves were state delisted in 2004 and federally in 2012, returning management back to the state and Indian tribes. Landowners will be able to control some problem wolves on their land and government trappers will remove problem wolves from depredation sites.

On April 22, 1970, 20 million people across America celebrated the first Earth Day. It was a time when cities were buried under their own smog and polluted rivers caught fire. Now Earth Day is celebrated annually around the globe. Through the combined efforts of the U.S. government, grassroots organizations, and citizens like you, what started as a day of national environmental recognition has evolved into a worldwide.......

by Swift Nature Camp

On April 22, 1970, 20 million people across America celebrated the first Earth Day. It was a time when cities were buried under their own smog and polluted rivers caught fire. Now Earth Day is celebrated annually around the globe. Through the combined efforts of the U.S. government, grassroots organizations, and citizens like you, what started as a day of national environmental recognition has evolved into a worldwide campaign to protect our global environment.

Since those early days, we have done a pretty good job cleaning up the planet. Yet , there is a staggering divide between children and the outdoors, child advocacy expert Richard Louv directly links the lack of nature in the lives of today’s wired generation-he calls it nature-deficit-to some of terribler childhood trends, such as the rises in attention disorders, obesity, and depression.

His recent book,Last Child in the Woods, has spurred a national dialogue among educators, health professionals, parents, developers and conservationists. It clearly show we and our youth need to spend time in nature.

Schools have tried to use nature in the class room for some time. At Holman School in NJ, Ms. Millar began an environmental project in the school’s courtyard. It has become quite an undertaking–even gaining state recognition. It contains several habitat areas, including a Bird Sanctuary, a Hummingbird/ Butterfly Garden, A Woodland Area with a pond, and a Meadow. My students currently maintain the Bird Sanctuary–filling seed and suet feeders, filling the birdbaths, building birdhouses, even supplying nesting materials! In addition, this spring they will be a major force in the clean up and replanting process. They always have energy and enthusiasm for anything to do with “their garden”.

Despite schools doing their best to get kids in nature , we as a nation have lost the ability to just send our kids out to play. Summer Camps are a great wayto fill this void. A recent study finds that todays parents overprotect their kids. Kids have stopped climbing trees, been told that they can’t play tag or hide-and-seek Not to mention THE STTICK and how it will put out someone’s eye.

Is the Internet and computers to blame for the decline in outdoor play? Maybe, but most experts feel it’s mom and dad. Play England says “Children are not being allowed many of the freedoms that were taken for granted when we were children, They are not enjoying the opportunities to play outside that most people would have thought of as normal when they were growing up.”

According to the Guardian, “Voce argued that it was becoming a ’social norm’ for younger children to be allowed out only when accompanied by an adult. ‘Logistically that is very difficult for parents to manage because of the time pressures on normal family life,’ he said. ‘If you don’t want your children to play out alone and you have not got the time to take them out then they will spend more time on the computer.’

The Play England study quotes a number of play providers who highlight the benefits to children of taking risks. ‘Risk-taking increases the resilience of children,’ said one. ‘It helps them make judgments,’ said another. We as parents want to play it safe and we need to rethink safety vs adventure.

Examples of risky play that should be encouraged include fire-building, den-making, watersports and climbing trees. These are all activities that a Summer camp can provide. At camp children to get outside take risks and play, this while being supervised by responsible young adults.

Swift Nature Camp is a Noncompetitive, Traditional OUTDOOR CAMP in Wisconsin. Our Boys and Girls Ages 6-15. enjoy Nature, Animals & Science along with Traditional camping activities. We places a very strong emphasis on being an ENVIRONMENTAL CAMP where we develop a desire to know more about nature but also on acquiring a deep respect for it. Our educational philosophy is to engage children in meaningful, fun-filled learning through active participation. We focus on their natural curiosity and self-discovery. This is NOT School.

In addition, regarlss of skill level, Swift Nature Camp has activities that allows kids to get better and enjoy. We promoted a nurturing atmosphere that gives each camper the opportunity to participate and have fun, rather than worry about results.

Our adventure trips that take campers out-of-camp on trips, such as biking, canoeing, backpacking. This is a highlight of all campers, they find it exciting to discover new worlds and be comfortable in them. We are so much more than a SCIENCE SUMMER CAMP.

Since the early days of Earth Day We have come a long way in protectin the planet Now its time to let our children play outside. This summer you can help your child appreciation nature by sending them to Swift Nature Camp. Summer Camp sets the foundation for a health life and is remembered for a lifetime by campers.

About the Author:

About the authors: Jeff and Lonnie Lorenz are the directors of Swift Nature Camp, a non-competitive, traditional coed overnight summer camp serving Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Midwest. Boys and Girls Ages 6-15 enjoy nature, animals & science along with traditional camping activities. Swift specializes in programs for the first time camper. To learn more clickAnimal Camps

Do you enjoy Nature? Do you like to take pictures?

Now it’s your chance to make the call! The National Wildlife Federation needs your vote!

Their Magazine has selected the finalists for this Photo Contest. The theme is “Nature in My Neighborhood.” Now we need YOU to help choose the winner!

Vote for your favorite image today!

The top vote-getter receives an official NWF field guide and, if not already a member, a free one-year membership to National Wildlife Federation. But we need to hear from you soon: Voting ends April 15!

It is a movie that all Swift Nature Campers will love!

Go to DISNEYNATURE

permalink=”http://www.swiftnaturecamp.com/blog”>

This earth day 2009 Walt Disney Studios is launching Disneynature a prestigious new production that will go to the ends of the earth to produce big screen documentaries. In the great tradition of Walt Disney Disney nature will offer spectacular movies about the world we live in...be sure to see it !